Unraveling the Lack of Correlation between RBP4 and MASLD: Insights from Gene Expression and Serum Level Analysis

L. Bertran 1, C. Aguilar1, T. Auguet

1, C. Aguilar1, T. Auguet 1,2,3 and C. Richart

1,2,3 and C. Richart *1

*1

1Department of Medicine and Surgery, Rovira i Virgili University, Reus, Spain

2Joan XXIII University Hospital, Tarragona, Spain

3Pere Virgili Health Research Institute, Tarragona, Spain

Submitted on 22 November 2025; Accepted on 15 December 2025; Published on 02 January 2026

To cite this article: L. Bertran, C. Aguilar, T. Auguet and C. Richart, “Unraveling the Lack of Correlation between RBP4 and MASLD: Insights from Gene Expression and Serum Level Analysis,” Trans. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1-6, 2025.

Abstract

Although previous evidence supports the involvement of retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), there are conflicting reports. Our aim was to evaluate the role of RBP4 in MASLD among a homogeneous cohort of women with morbid obesity (MO). We recruited 180 women with MO, including 40 with normal liver (NL), 40 with simple steatosis (SS), and 100 with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Serum levels of RBP4 were analyzed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). RBP4 hepatic mRNA expression was evaluated by a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). In this sense, we did not report significant differences in RBP4 circulating levels between hepatic histological groups. However, analyzing RBP4 hepatic mRNA expression, we observed decreased expression of RBP4 in MASH subjects compared to those with NL or SS. To conclude, in a homogeneous and sizeable cohort of women with MO and MASLD, our findings limit, contrary to previous proposals, the key role of RBP4 in relation to MASLD and MASH pathogenesis. Therefore, new studies are necessary in other study groups to validate the absence of this correlation.

Keywords: obesity; liver; MASLD; RBP4

Abbreviations: RBP4: retinol binding protein 4; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MO: morbid obesity; NL: normal liver; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index; COS: Centre for Omic Sciences; RIN: RNA integrity number; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase

1. Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a very recent term that refers to the presence of liver steatosis detected by imaging or biopsy, along with at least one metabolic alteration [1]. The global prevalence of MASLD is estimated at 30%, increasing in parallel with the prevalence of obesity [2]. Cardiovascular events are the primary cause of death in MASLD patients [3]. However, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), the severe form of MASLD, poses a higher mortality risk due to hepatic lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and, in some cases, liver fibrosis [4], which can progress to hepatic cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [5].

Retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) has been linked to MASLD in the context of insulin resistance [6]. Elevated RBP4 levels have been associated with increased insulin resistance [7, 8], a crucial factor in the development of MASLD [9]. Insulin resistance in adipose tissue triggers the release of free fatty acids, fostering ectopic fat accumulation and initiating hepatic steatosis. In the liver, this process exacerbates de novo lipogenesis and glycogen breakdown, aggravating the microenvironment and causing metabolic dysfunction, lipotoxicity, and the characteristic pro-inflammatory condition of MASH [10, 11].

Therefore, substantial evidence supports the involvement of the RBP4 metabolic pathway in the pathogenesis of MASLD [6]. However, conflicting reports exist in the literature. Animal models suggest that liver RBP4 overexpression promotes steatosis in mice through mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance [12]. In humans, initial evidence linking RBP4 with insulin resistance came from the study of Yang et al. [13], correlating elevated circulating RBP4 levels with increased hepatic insulin resistance in subjects with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Similarly, two studies in Chinese populations positively correlated circulating RBP4 levels with the presence of MASLD [14, 15]. On the contrary, other authors reported lower serum RBP4 levels in MASLD patients compared to controls, despite increased expression of RBP4 in the liver of those with hepatic involvement [16]. A study in Mexican-American patients indicated that plasma RBP4 levels correlated with T2DM but not with obesity or insulin resistance [17]. Furthermore, RBP4 levels were evaluated in patient groups according to liver histology (normal liver (NL), simple steatosis (SS), and MASH), revealing nonsignificant differences between the groups [18]. Our previous study supported these findings, noting higher levels of RBP4 in individuals with morbid obesity (MO) compared to lean patients [19].

Discrepancies in findings regarding the role of the RBP4 metabolic pathway in MASLD exist, and there is a lack of large and well-characterized cohort studies to differentiate between disease stages. Thus, this study aims to assess serum RBP4 levels in a cohort of 180 women with MO, with 150 participants further evaluated for RBP4 hepatic mRNA expression based on the liver histology defined by liver biopsy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects of the study cohort

In this study, we assembled a homogeneous cohort comprising 180 fertile women with MO (body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m²), all scheduled for laparoscopic bariatric surgery. To maintain homogeneity and avoid potential confounding factors, we exclusively recruited women, given the distinct metabolic and hormonal patterns between men and women [20, 21].

2.2. Anthropometrical and biochemical features

Methods of anthropometric and biochemical features were detailed [22].

Additionally, serum RBP4 levels were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at the Centre for Omic Sciences (COS) (EURECAT, Reus, Spain), following the manufacturer’s instructions (Human RBP4 Quantikine ELISA Kit, Ref. DRB400 Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

2.3. Liver histopathology

During bariatric surgery, liver biopsies were collected in RNAlater (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) solution at 4°C, and then processed and stored at -80°C. From all patients (n = 180), a liver sample was obtained for histopathological diagnosis, but only from a subset due to availability (n = 150), an aliquot of the sample was obtained for gene expression analysis. The samples for histopathological diagnosis were then preserved in a formaldehyde solution. These liver samples were scored and classified by an experienced hepatopathologist through eosin-hematoxylin staining according to Kleiner's criteria [23], in NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 100), with the latter presenting mild or moderate inflammation without the presence of hepatic fibrosis. According to liver samples used for gene expression analysis, the study groups were NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 70).

2.4. Gene expression analysis

The chosen method for RNA extraction was a combined method using the phenol/chloroform technique, followed by purification with the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Ref. 12183018A Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. A minimum of 20 mg of liver tissue was required for RNA extraction. Tissue disruption with phenol/chloroform was performed by sonicating three times for 10 seconds active and 10 seconds pause on ice using the Sonix Vibra-Cell 75186 sonicator (Artisan, Champaign, Illinois, USA) at 40% amplitude.

RNA quantification was performed with Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent TapeStation microfluidic electrophoresis system using the following reagents: RNA ScreenTape (Ref. 5067-5576), RNA ScreenTape Sample Buffer (Ref. 5067-5577), and RNA ScreenTape Ladder (Ref. 5067-5578).

RNA quality was evaluated using the RNA integrity number (RIN) parameter. For gene expression experiments, it was considered suitable when the RIN value was > 6 on a scale of 0 to 10. The final 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Ref. 18090010 Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was prepared with 2 μl of diluted cDNA, 5 μl of TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 0.5 μl of each TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in a final volume of 10 μl, following the manufacturer's manual. qPCR was performed on the QuantStudio 6 Pro Real-Time PCR Systems from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) using the 384-block. For this analysis, 18S was used as a housekeeping gene. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. This analysis was performed at the COS (EURECAT, Reus, Spain).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data analysis employed the SPSS/PC+ for Windows statistical package (version 27.0; SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed the variable distribution. Variables were presented as the median and interquartile range. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparative analyses. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of subjects

We classified our 180 MO women according to their hepatic histology into NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 100), as shown in Table 1. Subjects were comparable in terms of sex, age, BMI, waist-hip ratio, cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, and ALP levels. In this sense, subjects with MASLD (SS or MASH) exhibited elevated levels of glucose, HbA1c, insulin, triglycerides, AST, ALT, and GGT compared to those with NL histology. However, only subjects with SS had elevated levels of LDH and ferritin compared to NL subjects.

TABLE 1: Anthropometric and biochemical variables from our cohort of women with MO (n = 180) classified according to their hepatic histological diagnosis into NL, SS, and MASH.

|

Variables |

NL (n = 40) |

SS (n = 40) |

MASH (n = 100) |

|

Median (25th – 75th) |

Median (25th – 75th) |

Median (25th – 75th) |

|

|

Age (years) |

42.77 (36.86 – 51.03) |

42.98 (39.39 – 50.79) |

44.08 (39.63 – 51.23) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

44.27 (41.72 – 49.50) |

45.97 (43.17 – 50.97) |

46.15 (43.17 – 50.12) |

|

Waist-hip (m) ratio |

0.90 (0.84 – 0.95) |

0.91 (0.86 – 0.95) |

0.92 (0.87-0.99) |

|

Glucose (mg/dl) |

86.50 (74 – 99.25) |

109 (91 – 139.25)* |

105.50 (90.25 – 132.50)* |

|

HbA1c (%) |

5 (5 – 5.60) |

6.10 (5.40 – 7.20)* |

5.80 (5.20 – 7)* |

|

Insulin (mUI/L) |

7.94 (5.06 – 11.31) |

19.33 (11.14 – 31.27)* |

16.69 (11.66 – 26.52)* |

|

Triglycerides (mg/dl) |

96 (71.50 – 122.50) |

151 (113 – 188.75)* |

146.50 (121.25 – 207)* |

|

Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

168 (140.50 – 199.50) |

165 (144.50 – 190.37) |

164 (146.50 – 186) |

|

HDL-C (mg/dl) |

39 (33.90 – 47) |

36 (32 – 45) |

38.10 (33 – 43.67) |

|

LDL-C (mg/dl) |

101.60 (80.25 – 120.90) |

91.65 (77 – 114) |

92.75 (74.72 – 110.50) |

|

AST (UI/L) |

23 (19 – 39) |

35.50 (24.75 – 53.25)* |

33 (24 – 50.50)* |

|

ALT (UI/L) |

23.50 (16 – 43) |

36 (29 – 50.50)* |

34 (25 – 57.25)* |

|

GGT (UI/L) |

17 (12 – 23) |

26 (17.50 – 41.50)* |

23 (15 – 51)* |

|

ALP (UI/L) |

65 (51 – 78) |

68 (56 – 76) |

67 (58 – 78) |

|

LDH (UI/L) |

372 (331 – 423.75) |

427.50 (351.75 – 466.75)* |

394 (345.25 – 483.50) |

|

Ferritin (ng/ml) |

34 (17.42 – 75.50) |

77.50 (36.50 – 188.12)* |

48 (26.90 – 106) |

Data are expressed as the median and interquartile range. (*) Significant differences between NL and SS or NL and MASH were considered when p-value < 0.05 using the Mann-Whitney test. NL: normal liver; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; BMI: body mass index; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

3.2. Analysis of RBP4 serum levels

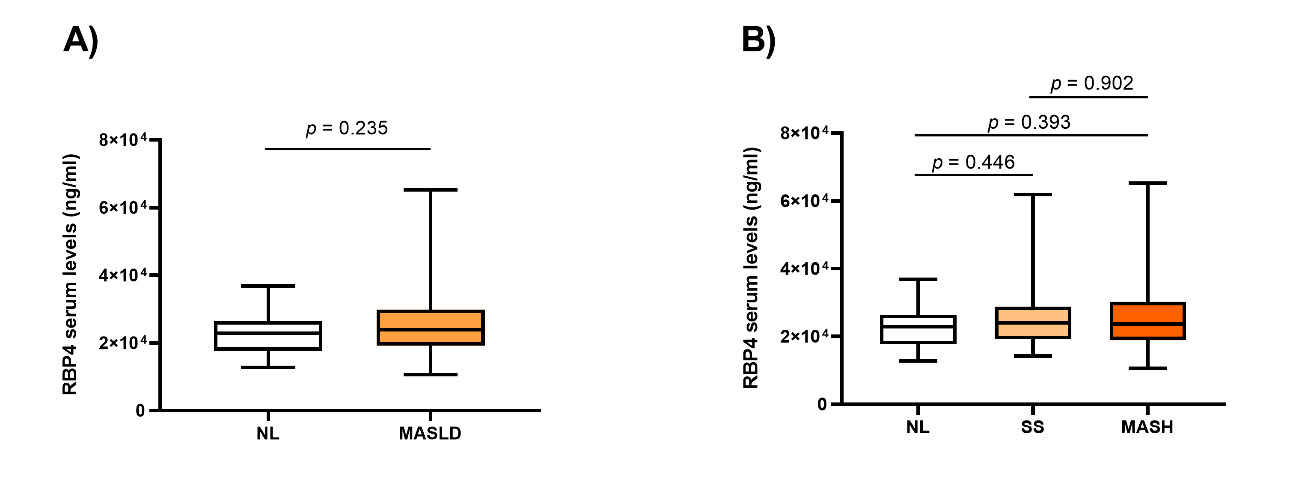

We conducted an assessment of RBP4 serum levels within the cohort of 180 women with MO. In this context, our analysis revealed non-significant differences when comparing subjects based on the presence of MASLD (Figure 1A), as well as between different hepatic histopathological groups (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1: Graphical representation of RBP4 serum levels in the different study groups. A) Between NL (n = 40) and MASLD (n = 140); B) Between NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 100). NL: normal liver; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; RBP4: retinol binding protein 4. Differences between groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test, and only p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The box plot was created using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

FIGURE 1: Graphical representation of RBP4 serum levels in the different study groups. A) Between NL (n = 40) and MASLD (n = 140); B) Between NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 100). NL: normal liver; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; RBP4: retinol binding protein 4. Differences between groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test, and only p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The box plot was created using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

3.3. Gene expression analysis of hepatic RBP4

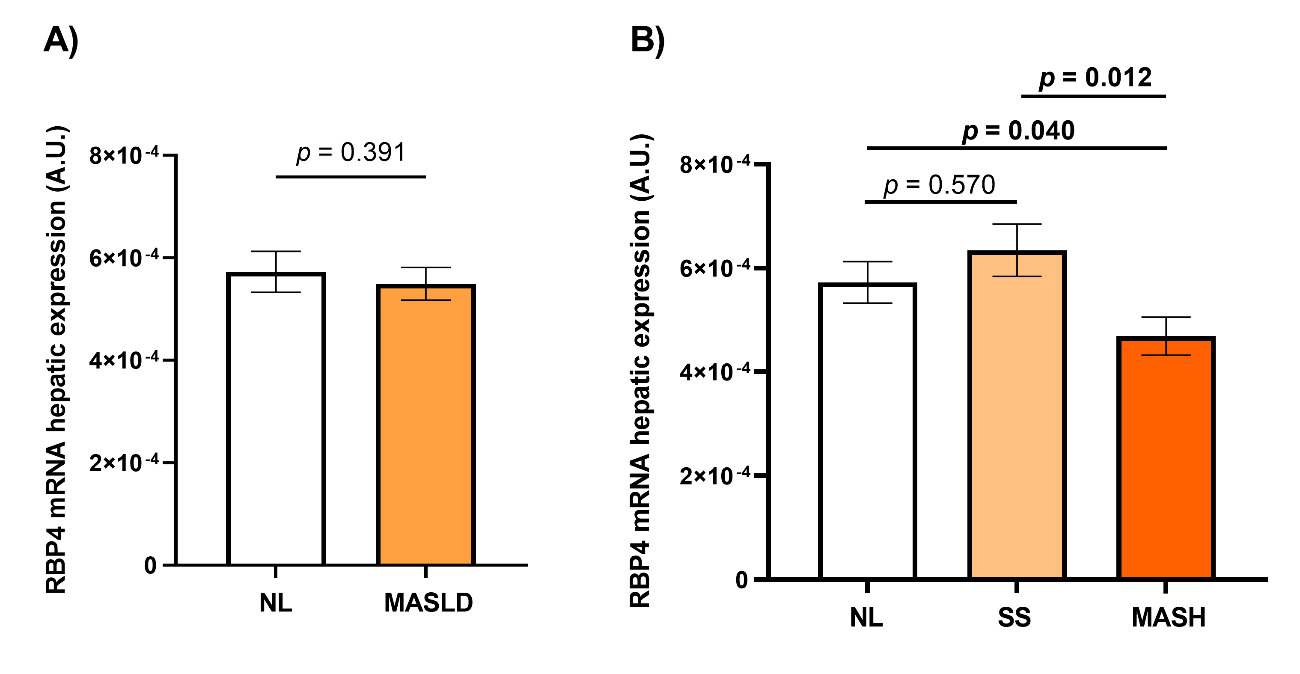

Then we performed a gene expression analysis of RBP4 in liver samples, taking into account the histopathological diagnosis of the liver. On one hand, no significant differences were observed between the NL and MASLD groups (Figure 2A). On the other hand, when evaluating RBP4 hepatic mRNA expression based on NL, SS, or MASH groups, we observed decreased expression of RBP4 in MASH patients compared to those with SS and those with NL histology. However, no significant differences were found in the other comparisons (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2: Graphical representation of the relative expression of RBP4 hepatic mRNA in the different study groups. A) Between NL (n = 40) and MASLD (n = 110); B) Between NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 70). NL: normal liver; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; RBP4: retinol binding protein 4; A.U.: arbitrary units. Differences between groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test, and only p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (bold). The bar graphs were processed using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

FIGURE 2: Graphical representation of the relative expression of RBP4 hepatic mRNA in the different study groups. A) Between NL (n = 40) and MASLD (n = 110); B) Between NL (n = 40), SS (n = 40), and MASH (n = 70). NL: normal liver; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; SS: simple steatosis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; RBP4: retinol binding protein 4; A.U.: arbitrary units. Differences between groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test, and only p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (bold). The bar graphs were processed using GraphPad Prism (version 8).

3.4. Gene expression analysis of liver RBP4 according to MASH parameters

As we observed notable differences in RBP4 liver expression within the MASH group, we aimed to further investigate RBP4 hepatic expression based on the degree of lobular inflammation and hepatocellular ballooning, the main characteristics of MASH. Our findings indicated a lower hepatic mRNA expression of RBP4 in subjects with moderate inflammation compared to those without inflammation (p = 0.016). Furthermore, liver expression of RBP4 was decreased in subjects with a mild degree of ballooning compared to those without this histological characteristic (p = 0.019).

4. Discussion

This study provides new evidence on the role of RBP4 in a homogeneous cohort of MO women with biopsy-proven liver diagnoses. It includes analyses of serum levels and liver mRNA expression; of the latter, there is scant previous evidence. On one hand, we did not report significant differences in RBP4 circulating levels between liver histological groups. On the other hand, significantly lower mRNA expression of RBP4 was found in the livers of women with MASH compared to those with NL or SS.

Although it is well known that RBP4 levels tend to be increased in subjects with obesity due to its association with insulin resistance and lipid accumulation [15, 24], we did not find significant differences in RBP4 serum levels when we compared our MO women with NL and MASLD. In a previous study, we found that MO women with MASLD had higher levels of RBP4 than MO women with NL [19]. In this regard, some studies also reported higher levels of RBP4 in MASLD subjects compared to controls [15, 25–28]; however, these MASLD subjects were diagnosed by ultrasound and were composed of heterogeneous groups in terms of sex and BMI. On the other hand, Schina et al. [16] reported decreased levels of RBP4 in MASLD subjects, and Polyzos et al. [29] reported non-significant differences in this comparison, just like in the current study, which included in both articles MASLD subjects diagnosed by liver biopsy as well as our participants. These discrepancies can be explained by the diagnostic method, since liver biopsy allows a more accurate diagnosis of the disease [30], as well as by the heterogeneity in terms of sex and weight of the study participants. In addition, in the case of studies with patients diagnosed with liver biopsy, the groups were composed of a small number of patients, making validation difficult [31].

Furthermore, we did not find significant differences in RBP4 circulating levels compared to NL, SS, and MASH. In this regard, some studies also did not report significant differences between histological groups in biopsy-proven MASLD cohorts [16, 32, 33].

Although it has been postulated that the association of circulating RBP4 with MASLD is due to its induction of de novo lipogenesis, disruption of fatty acid oxidation, and exacerbation of insulin resistance [31], studies in human subjects show conflicting results, so that the role of RBP4 in MASH appears to be more complex than previously described and needs to be further investigated in homogeneous and larger cohorts. In any case, it appears that serum levels of RBP4 cannot be a biomarker of MASLD or MASH, as there is no relationship with the physiopathology.

Later, we observed significantly decreased mRNA expression of RBP4 in liver samples from women with MASH compared to those with NL or SS. In this context, previous immunohistochemical analyses of RBP4 protein expression in liver samples showed that subjects with MASLD had higher RBP4 expression than participants with NL, and that this happens again in patients with MASH compared to subjects with SS [16]. Furthermore, it was suggested that RBP4 expression has a positive correlation with MASH severity and hepatic lobular inflammation [34], contrary to our findings in this regard. In any case, the MASH participants in these two studies had different degrees of fibrosis; meanwhile, our MASH subjects are in an early stage and do not present liver fibrosis. Additionally, we performed mRNA expression quantification by qPCR, while the other studies used immunohistochemical detection of RBP4 protein, which cannot be compared.

On the other hand, comparing our current study with our previous article on RBP4 in MASLD, we found that the expression of hepatic mRNA of RBP4 has similar values between women with NL, SS, or MASH [19]. Meanwhile, we have reported a lower expression of RBP4 mRNA in liver samples from subjects with MASH compared to participants with NL and SS. These discrepancies can be explained because we previously included a small cohort of MASH subjects, but now we have analyzed 70 subjects with biopsy-proven MASH. There are no further studies evaluating RBP4 hepatic mRNA expression in relation to MASLD or MASH.

Although it has been suggested that increased RBP4 expression in the liver promotes the release of proinflammatory cytokines [31], and therefore, it would make sense to find elevated RBP4 expression in the MASH stage, results in human models are scarce. Moreover, in adipose tissue, it has been shown that although RBP4 could be a proinflammatory cytokine, it tends to show reduced expression in an inflammatory environment [35], probably as an autoregulation of the RBP4 action. In this sense, our results suggest that the same effect could occur in the liver. In any case, this fact seems to reject a primary role of RBP4 in the pathogenesis of MASH, but it should be intensively analyzed in further studies in human subjects.

This study provides new evidence on the relationship between RBP4 and MASLD; however, there are certain aspects that we must consider. This study has only been evaluated in MO women, but we wanted to first study a homogeneous cohort in terms of sex, age, and weight with an accurate histological diagnosis. Studying patients with MO is necessary because approximately 90% of these patients have MASLD [36], and a liver biopsy can be obtained during bariatric surgery, which is less risky than a percutaneous liver biopsy. Also, the liver biopsy allows a more appropriate diagnosis of the stages of MASLD than imaging methods [37]. We believe that we have provided a sufficiently large cohort compared to previous studies, of 180 women with MO, and 100 of whom had MASH in the early stages. However, we plan to perform validation studies in larger and sex-matched cohorts for a more exhaustive evaluation of the role of RBP4 in MASLD. Finally, we believe that we have conducted a comprehensive study that analyzes serum levels and expression of RBP4 in liver tissue. However, it is difficult to discuss these results given the lack of comparable studies of RBP4 in relation to MASLD. In this regard, we encourage further studies to be carried out for a better understanding of the findings.

5. Conclusion

In a homogeneous cohort of women with MO with a liver biopsy-proven diagnosis, we reported no significant differences in RBP4 circulating levels between liver histological groups. However, we found significantly lower RBP4 mRNA expression in the liver of women with MASH compared to those with NL or SS, suggesting that RBP4 could not be involved in the pathogenesis of MASH. In any case, further studies need to be carried out for a better understanding of these findings.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Fundació URV [grant number IT-20041S].

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Fundació URV for its administrative support and EURECAT for its technical support.

References

- W. K. Chan, K.-H. Chuah, R. B. Rajaram, L. L. Lim, J. Ratnasingam, and S. R. Vethakkan, "Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review," Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 197–213, Sep 2023.

- M. H. Le et al., "2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis," Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 2809-2817.e28, Dec 2022.

- P. S. Dulai et al., "Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta?analysis," Hepatology, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 1557–1565, May 2017.

- S. Singh, A. M. Allen, Z. Wang, L. J. Prokop, M. H. Murad, and R. Loomba, "Fibrosis Progression in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver vs Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Paired-Biopsy Studies," Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 643-654.e9, Apr 2015.

- S. R. Karuthan, P. S. Koh, K. Chinna, and W. K. Chan, "Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer and Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging systems for prediction of survival among Hepatocellular Carcinoma patients," Medical Journal of Malaysia, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 199–204, Mar 2021.

- T. E. Graham et al., "Retinol-Binding Protein 4 and Insulin Resistance in Lean, Obese, and Diabetic Subjects," The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 354, no. 24, pp. 2552–2563, Jun 2006.

- A. A. Bremer, S. Devaraj, A. Afify and I. Jialal, "Adipose Tissue Dysregulation in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome," The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 96, no. 11, pp. E1782–E1788, Nov 2011.

- X. Wang, Y. Huang, J. Gao, H. Sun, M. Jayachandran and S. Qu, "Changes of serum retinol-binding protein 4 associated with improved insulin resistance after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in Chinese obese patients," Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 7, Dec 2020.

- K. M. Utzschneider and S. E. Kahn, "The Role of Insulin Resistance in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease," The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 91, no. 12, pp. 4753–4761, Dec 2006.

- F. Favaretto et al., "GLUT4 Defects in Adipose Tissue Are Early Signs of Metabolic Alterations in Alms1GT/GT, a Mouse Model for Obesity and Insulin Resistance," PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 10, p. e109540, Oct 2014.

- S. Huang and M. P. Czech, "The GLUT4 Glucose Transporter," Cell Metabolism, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 237–252, Apr 2007.

- Y. Liu et al., "Retinol-Binding Protein 4 Induces Hepatic Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Promotes Hepatic Steatosis," The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 11, pp. 4338–4348, Nov 2016.

- Q. Yang et al., "Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes," Nature, vol. 436, no. 7049, pp. 356–362, Jul 2005.

- X. Chen et al., "Retinol Binding Protein-4 Levels and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A community-based cross-sectional study," Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 45100, Mar 2017.

- X. Wang et al., "Circulating retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with the development and regression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease" Diabetes & Metabolism, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 119–128, Apr 2020.

- M. Schina et al., "Circulating and liver tissue levels of retinol?binding protein?4 in non?alcoholic fatty liver disease," Hepatology Research, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 972–978, Oct 2009.

- A. O. Chavez et al., "Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with impaired glucose tolerance but not with whole body or hepatic insulin resistance in Mexican Americans," American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 296, no. 4, pp. E758–E764, Apr 2009.

- Z. Zhou, H. Chen, H. Ju and M. Sun, "Circulating retinol binding protein 4 levels in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis," Lipids in Health and Disease, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 180, Dec 2017.

- X. Terra et al., "Retinol binding protein?4 circulating levels were higher in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease vs. histologically normal liver from morbidly obese women," Obesity, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 170–177, Jan 2013.

- E. B. Geer and W. Shen, "Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance," Gender Medicine, vol. 6, pp. 60–75, Jan 2009.

- R. Lauretta, M. Sansone, A. Sansone, F. Romanelli and M. Appetecchia, "Gender in Endocrine Diseases: Role of Sex Gonadal Hormones," International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2018, pp. 1–11, Oct 2018.

- T. Auguet et al., "LC/MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis in Women with Morbid Obesity and Associated Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus," International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 9, p. 7761, Apr 2023.

- D. E. Kleiner et al., "Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," Hepatology, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 1313–1321, Jun 2005.

- Y. Flores?Cortez, M. Barragán?Bonilla, J. Mendoza?Bello, C. González?Calixto, E. Flores?Alfaro and M. Espinoza?rojo, "Interplay of retinol binding protein 4 with obesity and associated chronic alterations (Review)," Molecular Medicine Reports, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 244, Jun 2022.

- J. A. Seo et al., "Serum retinol?binding protein 4 levels are elevated in non?alcoholic fatty liver disease," Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 555–560, Apr 2008.

- H. Wu et al., "Serum retinol binding protein 4 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus," Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 185–190, Feb 2008.

- M. Boyraz, F. Cekmez, A. Karaoglu, P. Cinaz, M. Durak and A. Bideci, "Serum adiponectin, leptin, resistin and RBP4 levels in obese and metabolic syndrome children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," Biomarkers in Medicine, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 737–745, Oct 2013.

- S. Huang and Y. Yang, "Serum Retinol?binding Protein 4 Is Independently Associated With Pediatric NAFLD and Fasting Triglyceride Level," Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 145–150, Feb 2013.

- S. A. Polyzos, J. Kountouras, V. Polymerou, K. G. Papadimitriou, C. Zavos and P. Katsinelos, "Vaspin, resistin, retinol-binding protein-4, interleukin-1α and interleukin-6 in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," Annals of Hepatology, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 705–714, 2016.

- C. Shaw and S. Shamimi-Noori, "Ultrasound and CT-directed liver biopsy: Ultrasound and CT-Directed Liver Biopsy," Clinical Liver Disease, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 124–127, Nov 2014.

- H. Huang and C. Xu, "Retinol-binding protein-4 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease," Chinese Medical Journal, vol. 135, no. 10, pp. 1182–1189, May 2022.

- N. Alkhouri, R. Lopez, M. Berk, and A. E. Feldstein, "Serum Retinol-binding Protein 4 Levels in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease," Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 985–989, Nov 2009.

- S. R. Kashyap et al., "Triglyceride Levels and Not Adipokine Concentrations Are Closely Related to Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in an Obesity Surgery Cohort," Obesity, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1696–1701, Sep 2009.

- S. Petta et al., "High liver RBP4 protein content is associated with histological features in patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C and with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis," Digestive and Liver Disease, vol. 43, no. 5, pp. 404–410, May 2011.

- A. Yao-Borengasser et al., "Retinol Binding Protein 4 Expression in Humans: Relationship to Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Response to Pioglitazone," The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 7, pp. 2590–2597, Jul 2007.

- K. Riazi et al., "The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis," The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 851–861, Sep 2022.

- K. K. Mahawar et al., "Routine Liver Biopsy During Bariatric Surgery: An Analysis of Evidence Base," Obesity Surgery, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 177–181, Jan 2016.